The Day the Wurlitzer Music Died

October 29, 1965; the music didn't die, it just called Robert Gates to play the Tune

Crew of the USS Tom Clancy,

Happy almost Halloween!

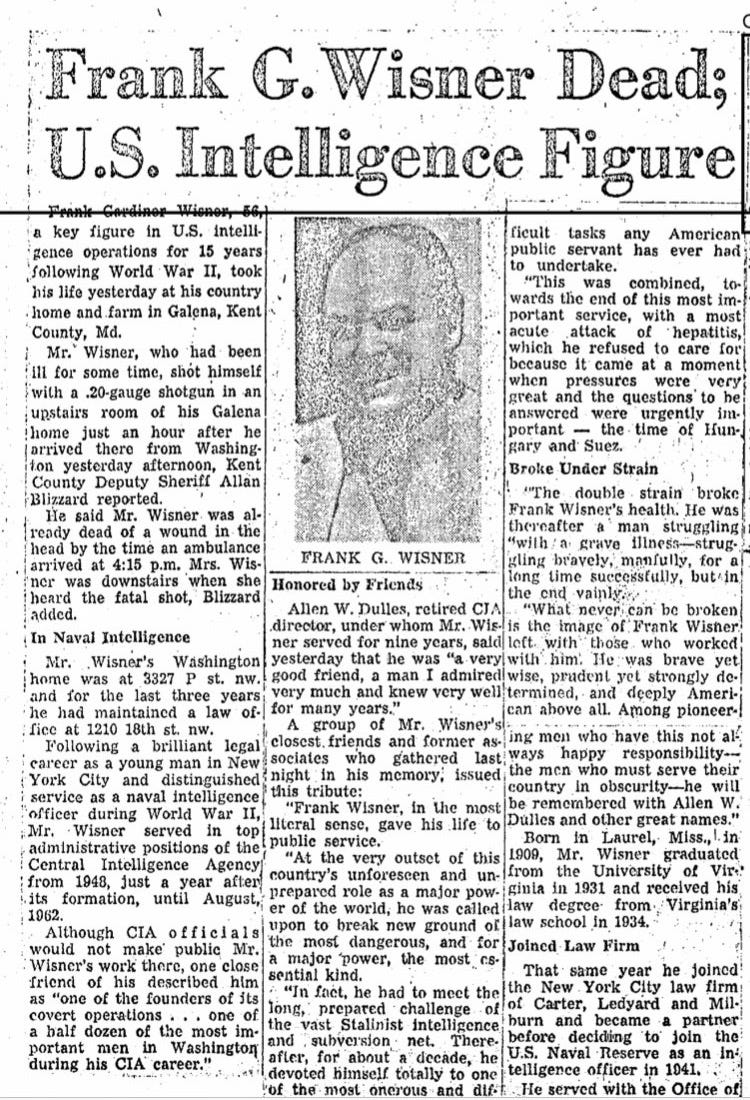

Today—October 29—is the 59th anniversary of the day in 1965 that Frank Wisner made his own quietus with his son’s shotgun on the second floor of an antebellum farmhouse on the Eastern Shore of Maryland.

Wisner is the man who—it seems more and more to me now—inspired and organized this whole program of covert propaganda through popular fiction we’ve been collectively exploring in the Hunt for Tom Clancy.

Remember, if we go back to the very beginning of The Hunt for Tom Clancy, Robert Gates plays a very critical role—post Hunt for Red October—in making sure Tom Clancy continues to write novels.

“In fact, right after The Hunt for Red October came out, I invited Tom Clancy to the Agency. I was then DDI (Deputy Director, Intelligence), so I had the job that in the movie version was played by James Earl Jones,” Gates told scholars at the University of Virginia’s Miller Center. “I invited Clancy to the director’s dining room for lunch.”

He invited him down to see the office, for “verisimilitude.” There, he lectured Clancy on the inaccuracies present in Hunt for Red October. “First, you’ll notice there’s no wood paneling, second, there’s no fireplace, third, there’s no Turkish coffee maker and fourth, there’s no admiral, but other than that you got it just right.”

Clancy wrote about the right kind of agency. The kind that didn’t assassinate, engage with the flesh trade to gather sexually coercive blackmail on leaders foreign and domestic, or drug unwitting subjects with experimental concoctions. Gates didn’t have much truck with any other spy novelists; he’d never read Ian Fleming, found LeCarre “too cynical.” He found the Jason Bourne series overly complicated. “The world that I knew wasn’t as complex as Ludlum’s,” Gates recalled. “I Just couldn’t keep it straight if it were.”

After lunch Gates made his pitch to get Clancy on the team. It was quite a journey for Clancy, who’d first had FBI agents raid his house after The Hunt for Red October was published, looking for evidence he’d been leaked classified information. He hadn’t with that one—the book was written using open source material—and it almost got him in trouble. With Bob Gates and the CIA’s help, the rest of his books would be informed by information leaked to him by senior government officials. “You’re probably going to write another book or two,” the man who would soon direct the Central Intelligence Agency, told the insurance salesman turned writer. The relationship was cemented. Years later, Gates ran into Clancy when they both spoke to “bright high school seniors.” Clancy told Gates, “You know, for the first several novels, I pretty much modeled Ryan’s career on yours.”

The relationship seemed to work pretty well, considering what then CIA director William Webster said to an audience of rich men at a Bohemian Grove Lakeside chat, three years later in the summer of 1988. Webster, the only man ever to run both the FBI and CIA, was impressed by how much the enthusiasm the groups he talked to as CIA director had for the business of spying: "Though I can't take credit…” he said, “the public has been primed by newspaper accounts, and by a number of popular books on espionage.”

For more on this, read The Hunt for Red October’s Leak.

Remember, Robert Gates was tutored in the higher echelons of intelligence by William Casey; Gates was Deputy Director (Intelligence) when Casey was Director of Central Intelligence. Here’s Bob writing Bill about Nicaragua in 1984.

So what does all this have to do with Frank Wisner’s suicide 59 years ago today, you might ask?

Well, for that answer we turn to the Wisner papers, housed in the University of Virginia’s Albert and Shirley Small Special Collections Library.

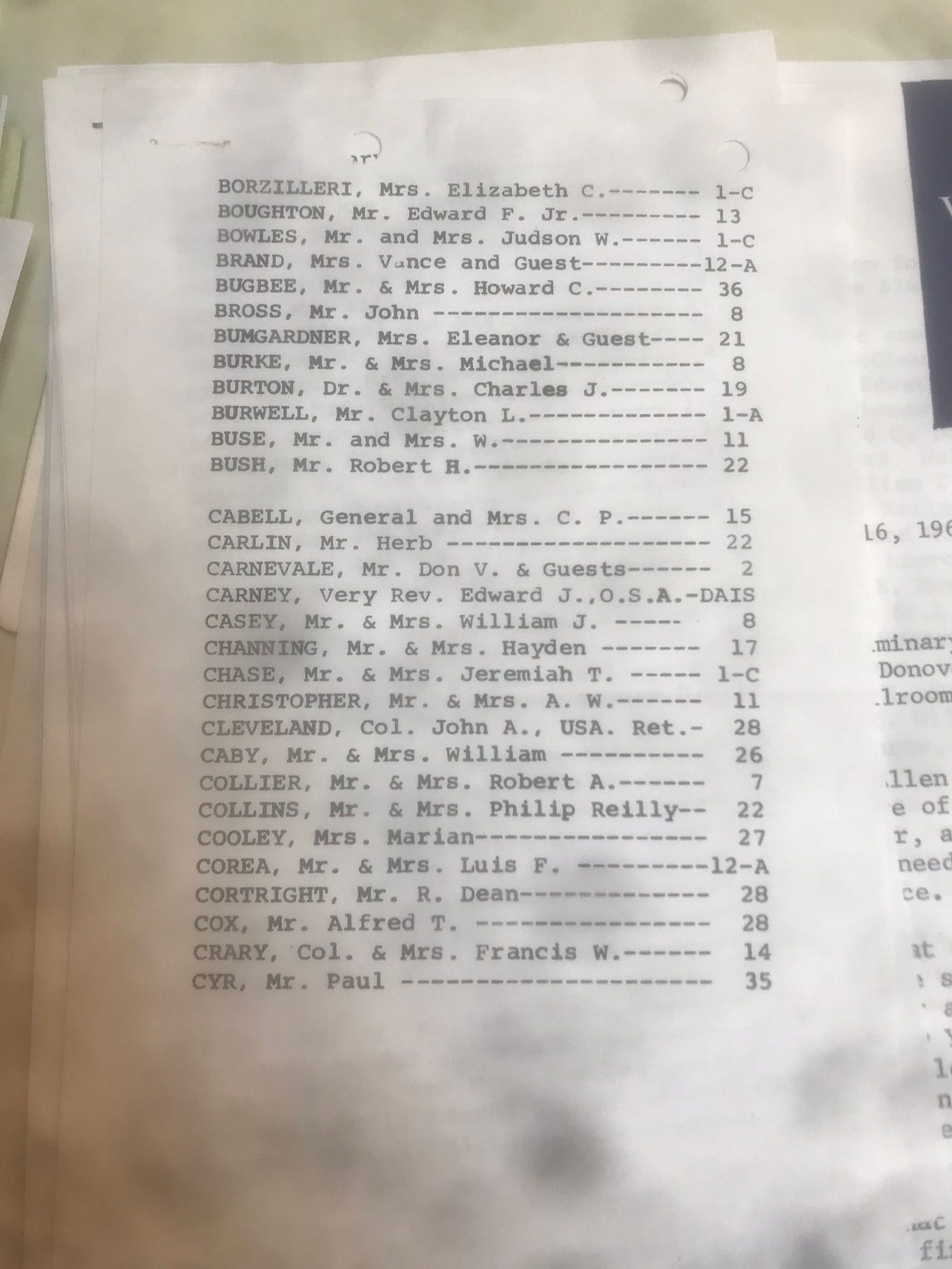

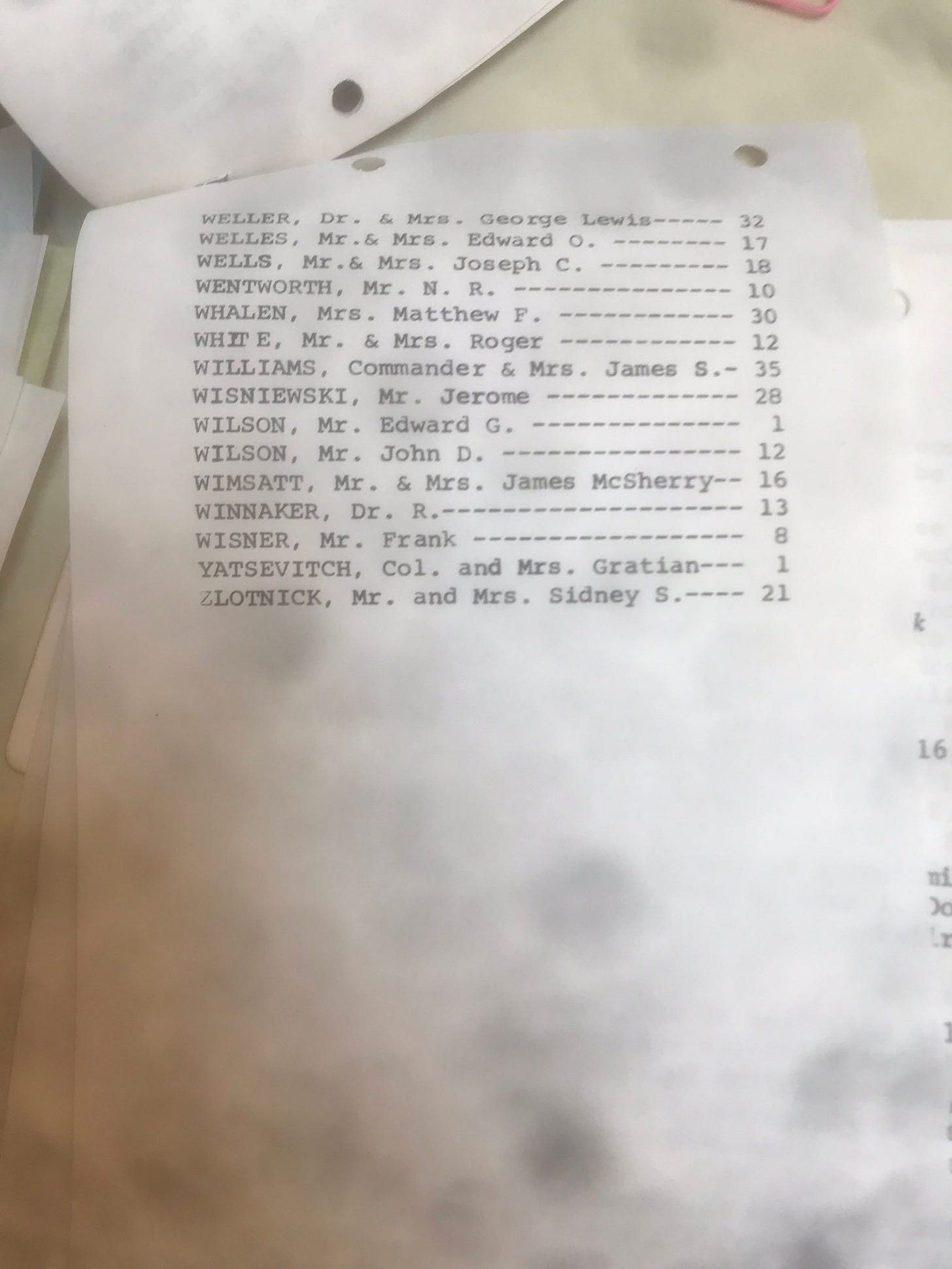

The previous year, on Dec 8, 1964 Frank Gardiner Wisner wrote a letter to Bill Casey and other friends from the Office of Strategic Services (OSS). The two had recently caught up at an OSS Reunion dinner at the Mayflower Hotel.

At the time, Casey was still a practicing lawyer (he’s widely credited as the man who invented the tax shelter) at the law firm of Hall, Casey, Dickler & Howley, housed in the pre-world War II 56 story Chanin Building at the corner of Lexington Avenue 42nd Street. Interestingly, the NYC Landmarks Preservation Commission, in 1978, described the Chanin Building this way (emphasis mine):

The first 17 stories completely cover the plot except on the center of the Lexington Avenue facade which is recessed above the fourth story. Major setbacks begin above the seventeenth story, forming a pyramidal base for the tower which rises uninterrupted from the thirtieth to the fifty-second story.

The two—Frank Wisner and William Casey—sat together at the dinner. Both were at Table 8.

Wisner had gotten really into spy novels over the previous year, providing notes, ideas and encouragement to a Scottish spy novelist named Helen MacInnes, who worked as a librarian. Her husband Gilbert Highet was an MI-6 spy and a Classical Scholar—Chairman of the Classics (Latin and Greek) department at Columbia University.