In Memoriam H.C.T.

Remembering Dr. Hannah Connor Tyson

New Mexico lost a whole lot of enchantment this year.

Two people I love dearly—my friend Hannah Tyson and my friend Monty Quintana—two of my best friends and favorite teachers, are now gone. I'm having trouble filling the void left by their absence. I still find myself pulling up their phone numbers and trying to call them up. If you'll forgive the digression from the normal discussion of spies, I'll use this dispatch of The Hunt for Tom Clancy to talk about Hannah Tyson. She’s a woman worth remembering, a woman impossible for me to forget.

"Even in our sleep, pain which cannot forget falls drop by drop upon the heart until, in our own despair, against our will, comes wisdom through the awful grace of God," goes a line by Aeschylus, quoted by Robert Kennedy after Dr. Martin Luther King was shot.

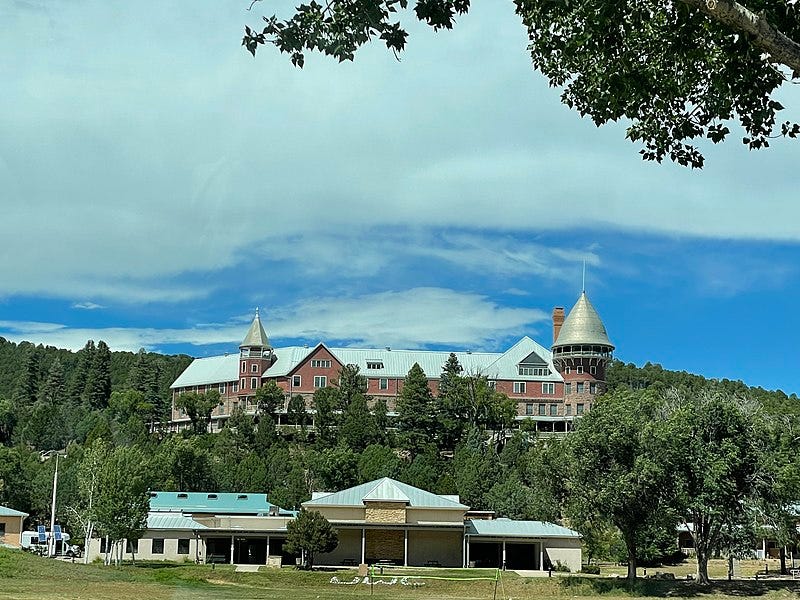

I remember writing those words in a sympathy card to Hannah when her husband Dan passed away over a decade ago. What else do you say when someone loses someone like that, after they spent so long together? I knew Dan, too, and liked him immensely; they were senior faculty at the United World College of the American West when I was a student there for my last two years of high school, Hannah was the best teacher I ever had in any school I’ve ever been to.

She was scary smart, didn't suffer fools, held high standards. The Armand Hammer United World College of the American West was only a two year sojourn for students, for the last two years of high school. When I got there, in 2000, Hannah was on sabbatical. My first year, her name was spoken in hushed tones, whispers: she was the faculty member you didn't want to disappoint, she was the faculty member you couldn’t bullshit.

We first-named all of our teachers at the UWC, which always struck me as odd with Hannah, I felt like I should be more formal in address, like I should call her Doctor Tyson; she just had that sort of bearing. She'd studied in a convent for twelve years and then left that life for a PhD in English Literature from Catholic University; Robert Lowell was her focus.

I worked harder in her class than I've ever worked in any class. I wanted to do my best for her. and for whatever reason, her brilliance motivated me to do the best. I still remember what I read in her English A1 class—drama included King Lear, Oleanna by David Mamet, and Equus; we analyzed poems by Michael Ondaatje, Wislawa Symborska, read novels by William Faulkner and Donna Tartt. This was in 2001 & 2002. For a high school English class.

She was a meticulous reader of our high school student papers, marking corrections in green rather than red. If you’ve ever seen The Paper Chase, you understand how it felt to step into her classroom; you’d better be prepared. I remember writing a short story for her based on a photographic prompt we picked from a folder of scenes she’d clipped from news magazines; the photo I got was of a man in Afghanistan getting his beard trimmed post overthrow of the Taliban. That was some serious foreshadowing, that story.

Our grading scale was from one to seven, seven being the highest, a grade Hannah rarely doled out. When I got a seven on a paper, I felt a feeling I’d never gotten in school—like I'd done something solid, I'd built a bridge and then watched a tank roll over it without collapsing. I can't tell you how much it meant to me. Sometimes, teachers really can make the difference.

Without her telling me I had talent, I wouldn't have been a writer. I knew she wasn't full of shit, or trying to make me feel good. If she said I was good at something, that meant I was good at something.

Years after taking her class, I dedicated my book "American Cipher: Bowe Bergdahl and the US Tragedy in Afghanistan" to two people: Dr. Hannah Tyson and Michael Hastings. Michael was already gone at that time—and now they're both gone. Shit, I still try to call Michael sometimes, and it's been almost a decade since that horrible day.

There's a lot of those ghost numbers in my phone, too many dead people in the digital rolodex, and even today I've found myself reaching for the phone to call Hannah. That hasn’t been possible for a couple weeks.

On November 6, as I was driving home from church on a sunny bright day, I got this text message from Hannah: "Hi Matt: the Journey is pretty much over—sending ❤️ . Been a ride with you!!"

I called her from the car; she was in the hospital. She'd contracted pneumonia, and nature take its course. I didn't argue, cajole, ask her to reconsider. Of course, that's all I could think about, I wanted her to fight, to beat this, to move past, to keep alive and keep being my friend, but I also knew that was selfish.

Over the past few years she'd been dealing with a terminal cancer diagnosis which she largely kept secret; it was another reason she'd moved back to New Mexico, better oncologists there. She'd gotten thinner each time I’d seen her, she was never big to begin with, she had trouble going and doing the things she liked to do, and the pandemic threw in a whole host of other complications.

When I saw her in September, on my way back from Idaho, she’d ordered in a feast for us to eat. It was our last meal, and she did it right, but it was clear that’s what it was. I cried when I left New Mexico.

She'd decided that this was it, and it was it.

I didn't have to like it, but I had to respect it. She always knew what she wanted.

I'd told her I was sorry I couldn't be there, sorry I couldn't hold her hand through the last part of the experience.

Honestly, I wasn't sure I could do that again; sitting in the Farmington, New Mexico hospital with my friend and brother Monty on his last days in April was brutal; he just wanted to go home to die, back to Dulce, back where he could see the Archuleta Mesa and the Rockies, but that's not the way we do death in this country, we don't do the dignity side of it. So he died in a hospital, as Hannah would.

"I've got plenty of people trying to do that," she told me, “but we all die alone, Matt.”

I practically hear her eyes rolling at me over the phone.

I thanked her for adopting me over these last twenty years; she'd never had biological children, and she treated me with a motherly kindness and concern. I told her I loved her, that I would miss her, that I would never forget her. I told her no lies.

She didn’t lie to me, either. Years ago, barely into my twenties when I told her I had a crush on someone, she’d told me the object of my crush wasn’t going to work out. “She’s too much woman for you, young man,” and she wasn’t wrong.

I could talk about things with her that were difficult to talk about with anyone else; I knew she would hear me, try to understand, and then formulate the best advice her megawatt brain could create.

She was always direct, blunt even, but it never seemed rude, because it never was rude. That directness and bluntness were buttressed by the elegance with which she expressed herself and knowledge that when she talked, she really knew what she was talking about, she really knew who she was talking to, and what they needed to hear to affect the change that needed to happen.

She was a genius at that.

I think about all the times I leaned on her: she helped me get through things post-war, the death of my friend Bob Kotlowitz, the death of my friend Michael Hastings, the deaths of many other friends. She read and critiqued my writing. She heard my frustrations with the writing world, she gave me perspective on the sadness after my divorce. She was my rock, a wispy Granite monolith of a woman, the type of person one could cling onto during rough winds.

I tried to be reliable for her, as well. I helped her move back to New Mexico, driving her car out to Santa Fe from Maryland shortly before my book came out, excited I could give her an early copy, let her see her name printed up front.

One time, a few years ago, when I was out in New Mexico for a week, her phone was stolen—I tracked it down on find my iPhone and we set off on an adventure to get it back; she'd seen writer Matt, but she hadn't seen infantryman Matt, and she saw a bit of him that day as we tracked down the phone and confronted the thief. We had fun!

When she wanted to get a new Corgi from a breeder in Tucumcari in October 2019, she asked if I would drive down with her, just to make sure everything was on the up and up—I noticed the dog breeder’s wife had the words “Love” and “Hate” tattoo’d on her knuckles, Night of the Hunter style, but no ill came of it. We came back with a lovely little guy named Gwilym, a loyal and dignified dog who kept her company for her last couple years.

The day we got the news officially via an email from the UWC alumni dude that Hannah shuffled off the mortal coin, my sister from another mister (and fellow UWC graduate) Kachi called me to commiserate. Hannah was incredibly kind to her during a difficult time in high school, when Kachi felt few other people had her back.

I told Kachi I'd felt the same love and patience from her, but at a different time, back when I was isolating and alienating friends right and left after the war. Hannah was patient, Hannah was kind, Hannah was there. She was, once again, wispy granite holding strong in high winds. The woman taught for decades and was important to so many people, influential in so many lives, just such a strong force, a person with a gift for unlocking people's potential.

Hannah was born in 1939, I was born in 1983. You'd think we wouldn't have much to relate to each other on. You'd be wrong. Inter-generational friendships are wonderful; both parties learn a lot. She took me to all the best restaurants in Santa Fe, gave me book recommendations. When I was around her, especially these last five years, I was conscious of the fact that she loved me with something bordering on unconditional, like a whacky son or grandson she'd never had. I loved her, too.

She was a brilliant and flinty New Hampshire native, not the type to milk her terminal diagnosis for sympathy, or even reveal it. She told me because we'd kept in touch since I graduated, with cards and emails and visits; I wrote her letters from college, from Afghanistan, from mental hospitals, from jail once.

She wrote me back, her handwriting a form of beautiful calligraphy. She knew me and death were on pretty solid terms, having interacted quite often, and that I could bear the burden she didn’t want to share with many others. I’m honored that she trusted me so much.

She'd retired from teaching at the UWC but kept on doing seminars for International Baccalaureate teachers. I saw her a few times a year for the past five years, stayed at her house a couple times when I was in Santa Fe.

I'm writing these words from a beautiful wooden standing desk, Mennonite built, that once belonged to Dan. Hannah gave it to me a few years ago, after I helped transport her car from the retirement community near Washington DC she'd gone to from New Mexico after Dan's passing.

My friend Doug and I loaded it up in a rented truck after Go Jii Ya 2019 and have used it every day since. This desk will be with me until the day I die. Each time I use it I will remember Hannah Tyson and what she taught me, both in the classroom and in my post-schooling life. I will remember to be grateful.

I will remember her example and, I’ll honor what she taught me, try to be the person she expected me to be. Mostly I will miss her, ferociously. The world is a colder place without her in it.

Since it fell into my lot, that today I should rise and she should not, I'll gently rise and softly call: Goodnight dear Hannah, joy be to you all.

As I think about this lovely obituary of a woman I knew many years ago, I am glad to think that she died shortly before the release of OpenAI's first public version of ChatGPT. I am sure she would have been deeply perturbed by the thought that humans are now offloading the effort and art of expression with the written word. Rest in peace, Hannah. You and Dan were legends.

“I will remember her example and, I’ll honor what she taught me, try to be the person she expected me to be.”

I cried reading that sentence. That sentence is all we can do on this side of existence to honor the dead. I’ve never been good at maintaining relationships like the one you had with Hannah, but the world is a better place because you did.